Aesthetic Citizenship and the Politics of Belonging

To be seen is not merely to be visible, it is to be recognised, legible, and valued within a social order. In contemporary society, this recognition is not simply granted by legal status or civic participation but increasingly mediated through the body. The way we dress, move, speak, and appear (our aesthetic presentation) functions as a powerful register of legitimacy.

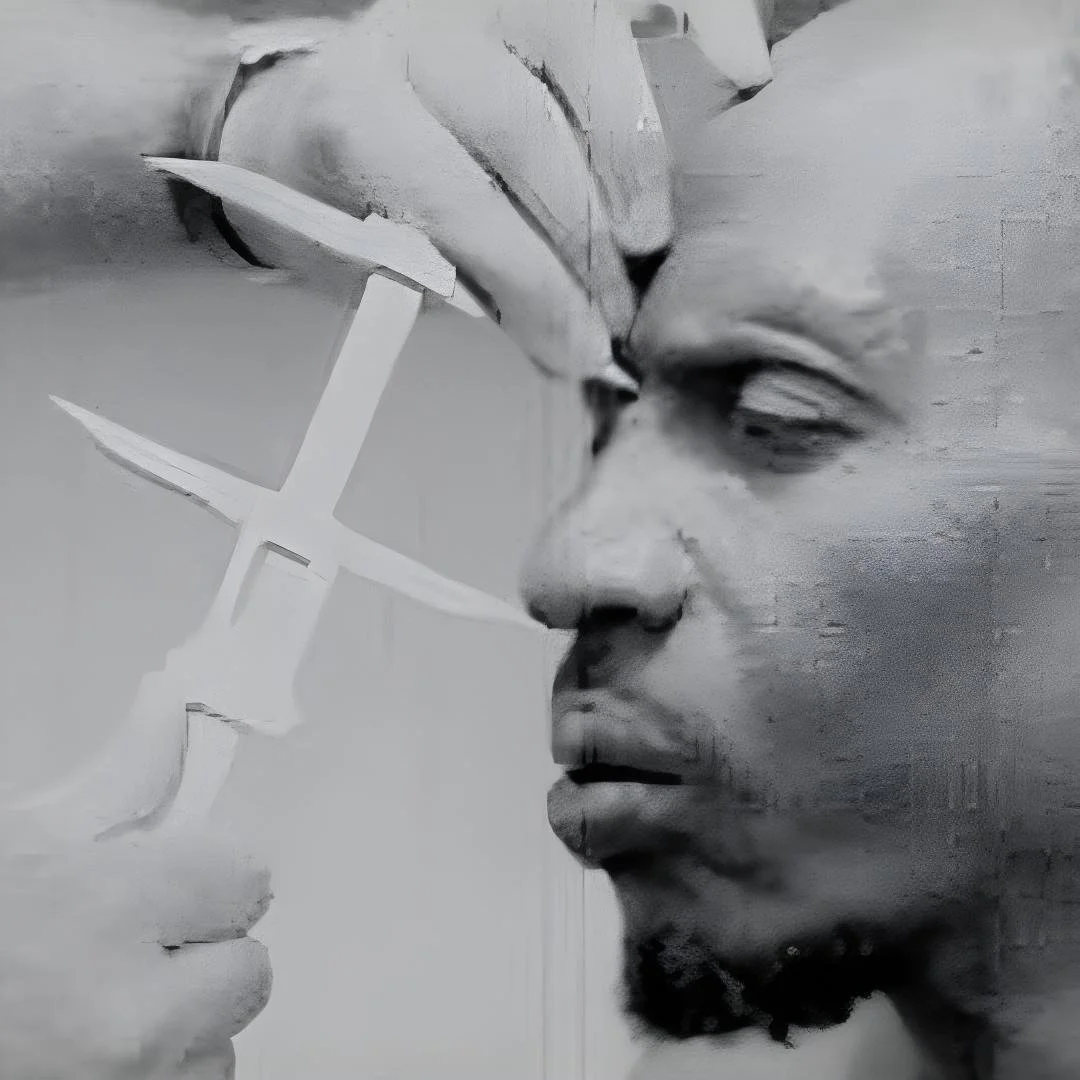

Phrenology and the Rwandan Genocide by Charles André. Belgian doctor examines a Rwandan man.

The concept of aesthetic citizenship interrogates the intersection between appearance and political belonging. It reveals how bodies are judged, included, or excluded from the protections of citizenship based on their conformity to normative ideals of beauty, order, and respectability.

To appear beautiful, orderly, and normative is to gain access to humanity. To fail at this aesthetic performance is to risk becoming illegible, or worse, disposable. Beauty and belonging are not neutral qualities; they are social filters through which the state and society determine who is grievable, who is worthy of attention, and who may be discarded without mourning.

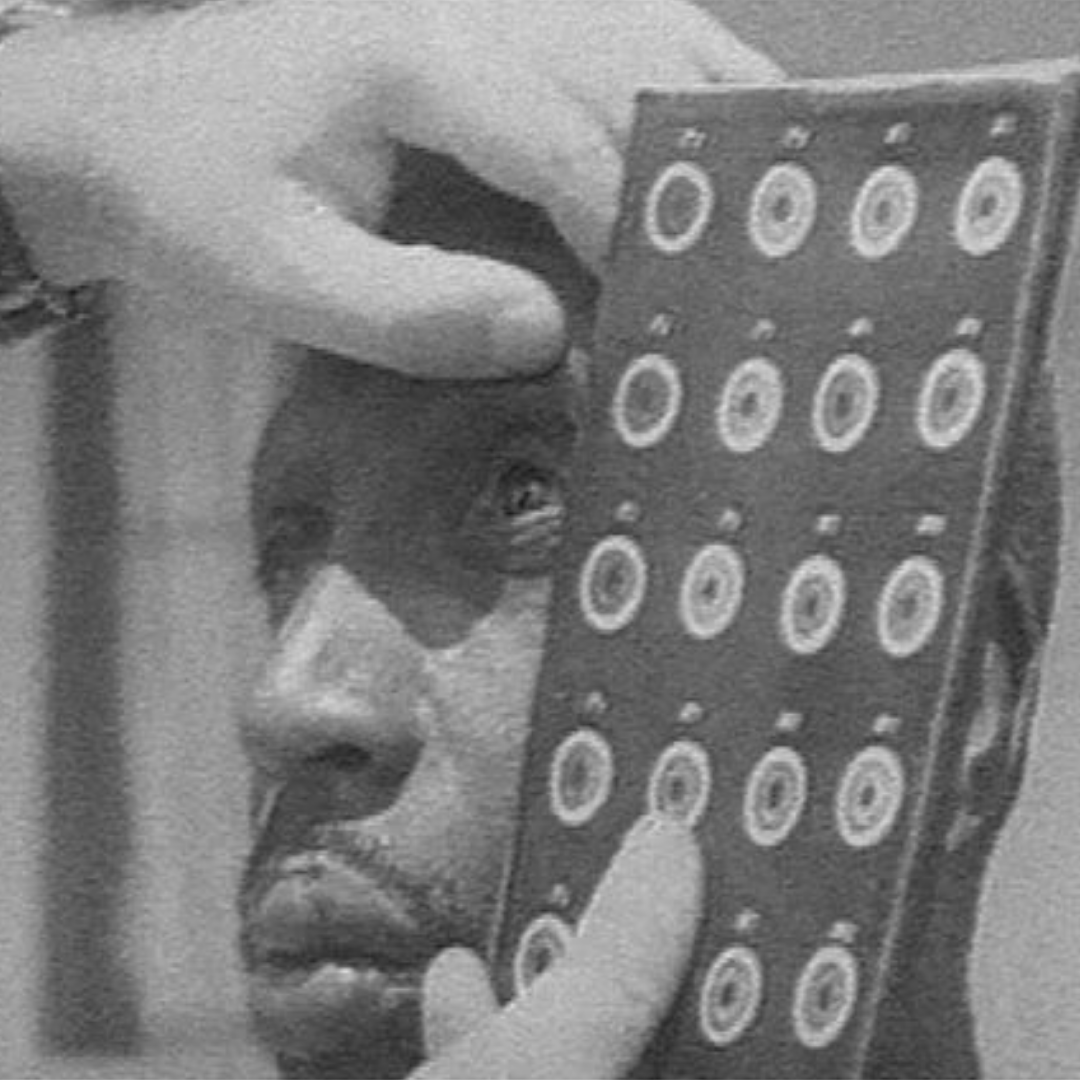

Photograph by Alvan S. Harper (1847-1911) titled “Woman in Dark Dress with Roses on Bodice” Photographed in Tallahassee, Florida between 1885 and 1910.

Beauty operates as a silent instrument of power. It enforces social hierarchies, masks structural violence, and disciplines bodies through subtle expectations of conformity. It is a political currency, one that determines who is recognised, protected, and afforded full personhood.

In this sense, the legibility of the body becomes a precondition for political legitimacy: one may hold rights on paper, yet if one does not meet the aesthetic standards imposed by institutions and communities, those rights remain conditional, selectively enforced, or withheld altogether. Skin tone, dress, gender presentation, body size, hair texture, and posture all become proxies through which belonging is adjudicated.

The violence of aesthetic citizenship is often silent, operating not through overt coercion but through habitual, everyday practices: the surveillance of gaze, the policing of posture, tone of voice, or attire. Under this regime, survival frequently demands self-erasure or self-modification. One may vanish into invisibility or contort oneself to align with dominant ideals, acceptable yet never fully recognised as belonging. Aesthetic citizenship thus underscores the uneasy tension between survival and belonging, showing how the body becomes a site of political negotiation in a society that evaluates not only rights but appearances.

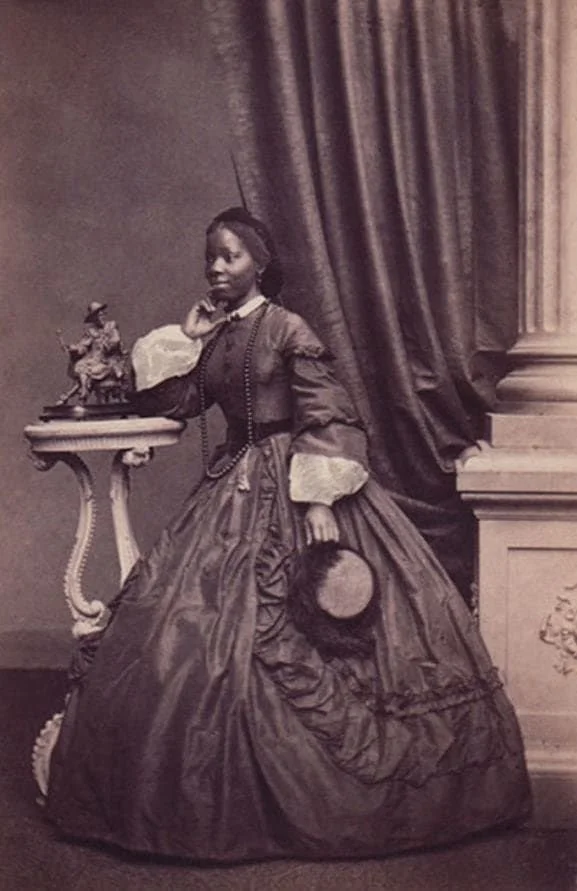

Sara Forbes Bonetta. Brighton, 1862. Photograph: Courtesy of Paul Frecker collection/The Library of Nineteenth-Century Photography